Boston Rubber Shoe Company

Reproduced from https://amp.wickedlocal.com/amp/37799767007:

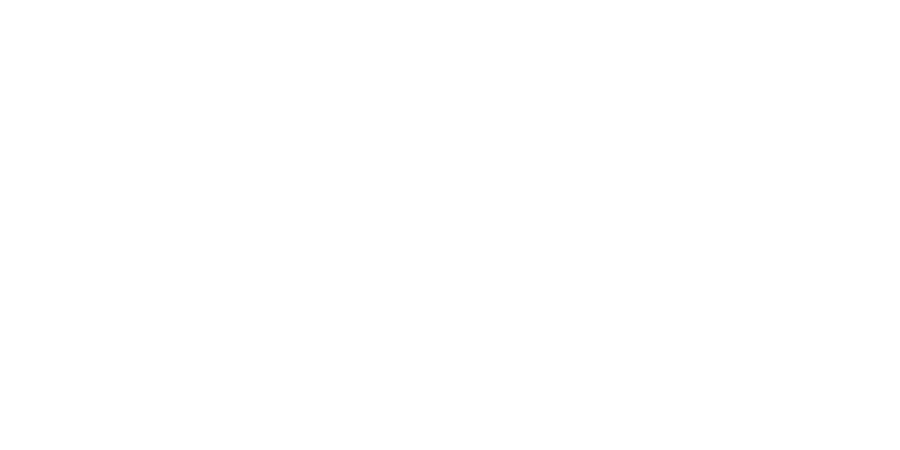

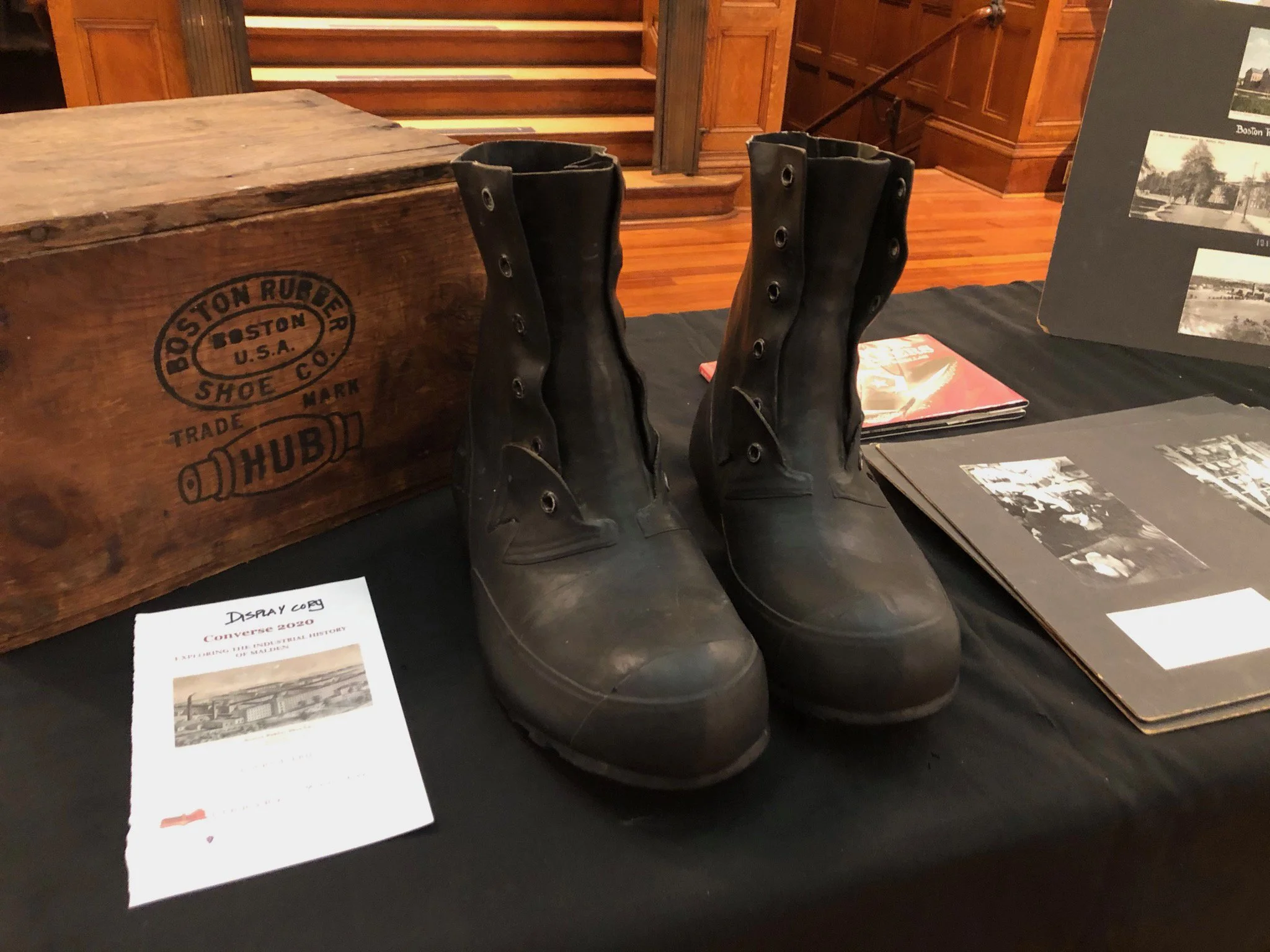

Elisha Slade Converse and his brother James Wheaton Converse founded the Boston Rubber Shoe Co. in 1853, manufacturing rubber boots and overshoes. The factory was located in Malden, with the head office and warehouse at 245 Causeway St. in Boston.

According to “The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography” by James T. White and Company, published in 1910, the business was originally incorporated as the Malden Manufacturing Co. with a capitalization of $175,000, and the Malden factory churning out 400 pairs of boots per day.

A fire destroyed the Malden factory on Nov. 2, 1875. According to “History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts” by Samuel Adams Drake, published in 1880, the fire, coupled with the existing depression, “caused the liveliest concern for the welfare of those who were suddenly deprived of their accustomed means of livelihood.”

“But by the aid of the benevolent and the care of the corporation,” the passage in the book continues, “the winter passed without the extreme inconvenience and suffering which were anticipated, and larger buildings and improved machinery soon gave evidence of the enterprise and courage of the company and its managers in the face of disaster and the discouragements which then prevailed.”

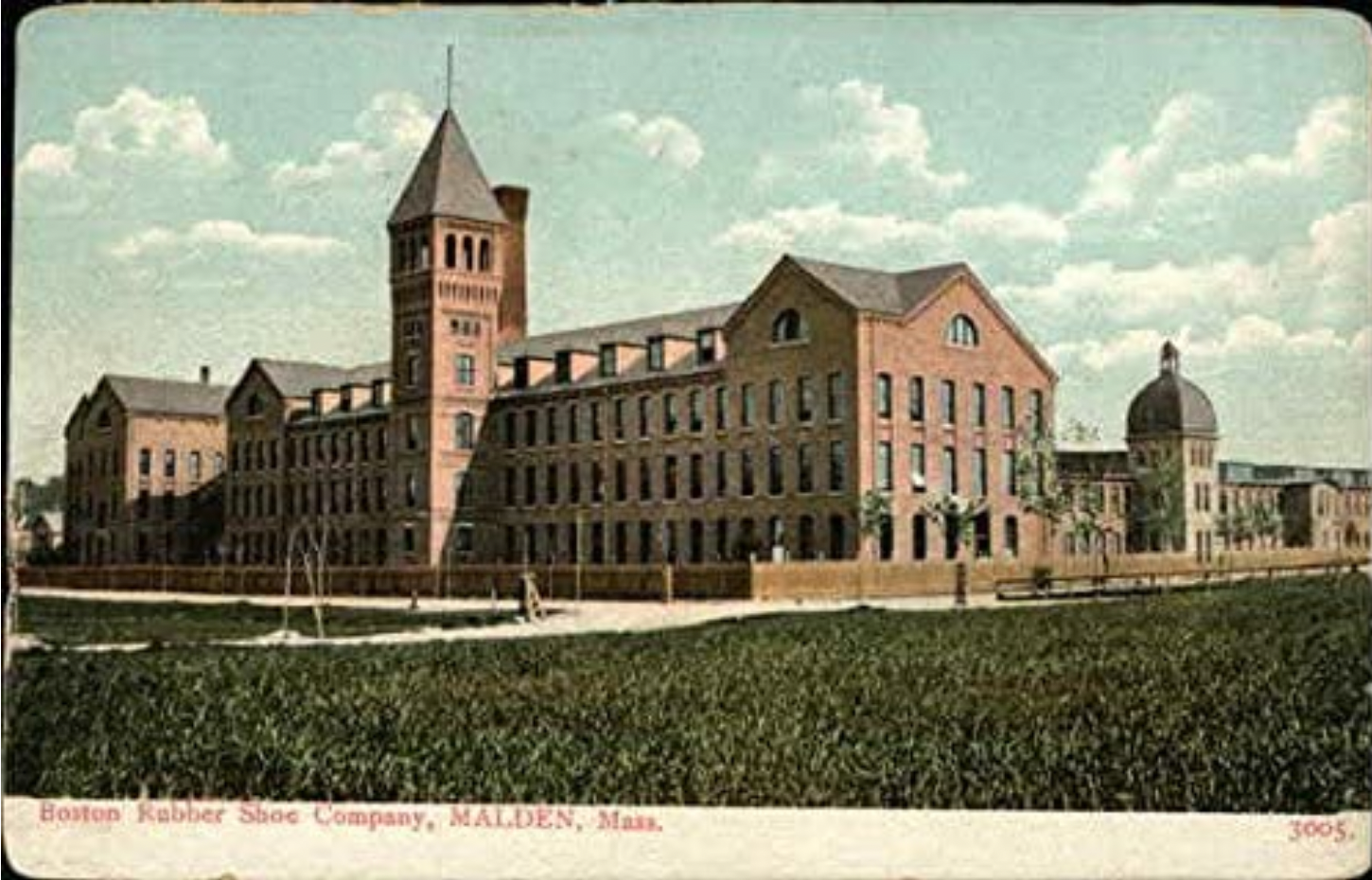

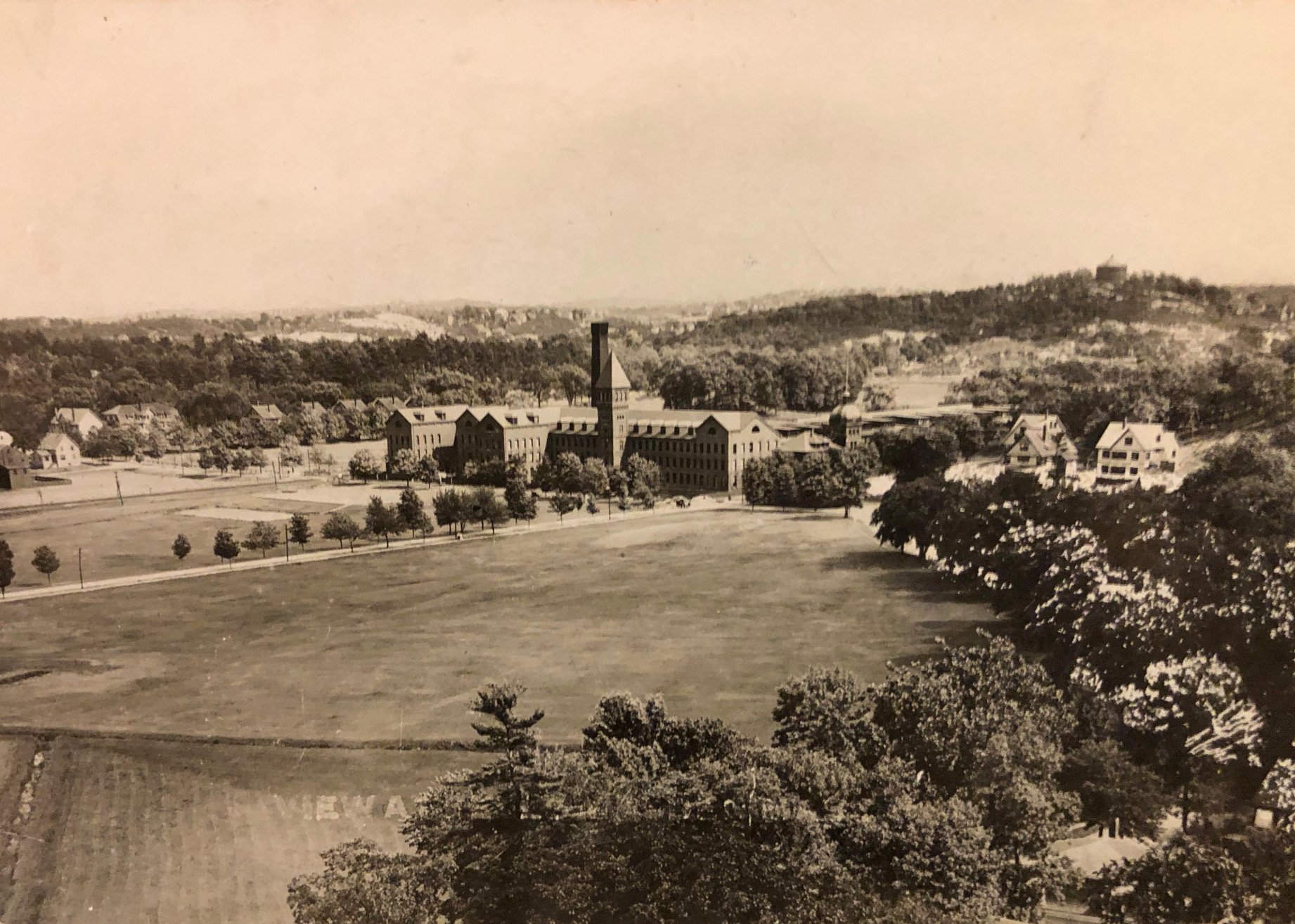

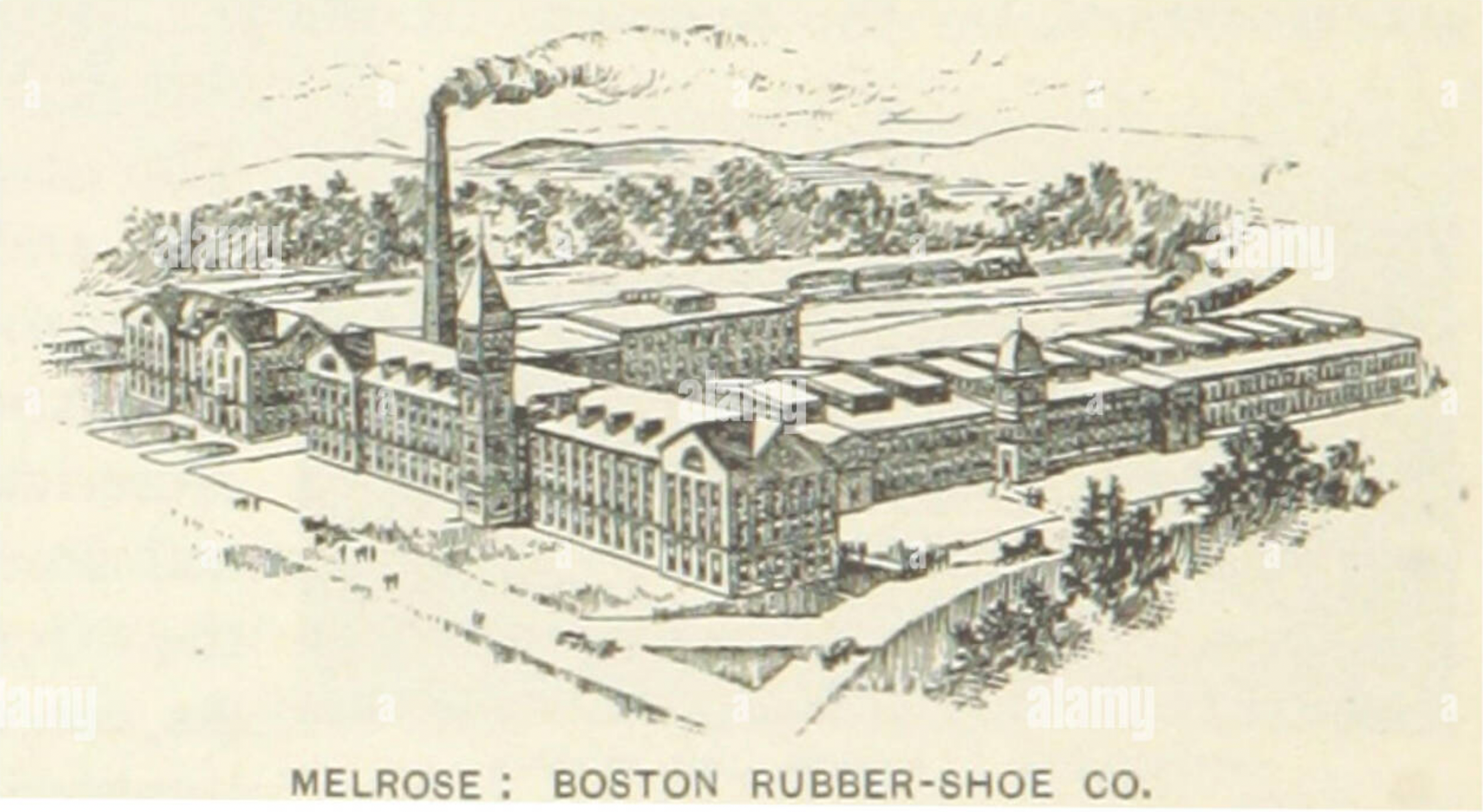

A new, larger factory was then built in Malden, employing 1,500 workers and producing 20,000 pairs of rubber shoes a day. By 1881, the company could not keep up with demands and built a second factory — “Converse No. 2” in Melrose — that opened in 1882.

By 1910, the Boston Rubber Shoe Co. had grown to a capitalization of $5 million, employing 3,500 people at both factories, and producing a daily output of 55,000 pairs of rubber boots and shoes.

Let there be light … and power

In 1970, Tom Ford, a partner at Melrose’s Tasco Realty, and his partners bought 72 Stone Place — known as “Converse No.2,” the second Boston Rubber Shoe Co. factory that opened in 1882 — from Stoneham resident Angie Crockett. Except for the building at 37 Washington St., on the south end of the complex in Melrose, the buildings are all relatively narrow. “Thirty-seven Washington, which is the building at that end of the complex, is wider. The reason it’s wider is because, I think, that the time that building was built, I’m guessing, there was electricity,” he said. “The reason this building is so narrow and Marty’s Furniture is so narrow is they needed light from the windows to work because there were no electric lights. A lot of people don’t understand that. I sure didn’t understand that when I bought the building.”

While the Marty’s Furniture building is still wider than Converse No. 2, it is only two stories high instead of four stories. Ford said when it was first built, the Marty’s building had dormers all along the roof to allow light in. In a drawing of the complex from 1892, framed and sitting atop a cabinet in Ford’s office, 13 dormers can be seen across the top of the Marty’s building.

“Those are gone now,” Ford said. “I’m sure they were a source of a lot of leaks and so forth. This building [Converse No. 2] is quite narrow and has very big windows.”

Without electricity, the Boston Rubber Shoe Co. had to find other means to power their machinery. Ford said in 1882 most factories were either powered by a steam engine or a watermill. So most of the mills were built on rivers to get the water.

Towards the back of complex, between 72 Stone Place and 78 Stone Place, an enclosed and immense warehouse-size room currently sits, near the large chimney that towers over the area. Ford said that the room previously had no roof, as it housed two steam engines used to power the Boston Rubber Shoe Co.

The company owned two, Ford surmised, because they constantly needed power, so the engines alternated as backup for one another in case of a breakdown. Also, that area featured a train track that elevated above the floor in the engine room, where a ‘gondola’ car would open up a hinged bottom door and dump coal onto the ground below to power the engines.

One of the earliest sprinkler systems

The sprinkler system itself is a historical artifact. Ford said the sprinkler system installed in 1882 is still the sprinkler system in use today, grandfathered-in and in surprisingly good shape. He said sprinkler systems can either be ‘wet’ or ‘dry,’ and explained that most modern systems are dry, meaning that the pipes contain compressed air and when the sprinkler’s fuse melts — due to heat from a fire — the air escapes, flipping a valve that fills the pipes with water.

While 37 Washington St. — the newest building on the complex — has a dry system, the rest of the buildings feature a ‘wet’ system, meaning the pipes are always filled with water.

“You might think it would rust, but in order to rust it needs oxygen, so once the thing is filled, the iron takes the oxygen out of the water and there’s no more oxygen left, so it stops rusting,” Ford said. “It’s actually a pretty stable system, believe it or not, and it turns out our wet systems are in better shape than our dry systems because there’s less rusting. A strange little fact, and it’s all because of the chemistry of the situation.”

On Aug. 11, 1874, Henry S. Parmelee of New Haven, Conn., obtained the first U.S. patent for a sprinkler head, and the first U.S. patent for a sprinkler system was issued to Philip W. Pratt of Abington on Sept. 17, 1872 — all of which is to say, as Ford notes, that the Converse No. 2 sprinkler system is probably one of the earliest sprinkler systems in existence.

The sprinkler heads — and trout — are now gone

Ford said when Tasco Realty first bought the building, they called a sprinkler system company to inspect the system. The sprinkler heads feature fusible plugs that melt at a certain temperature, allowing the water to spray. The company said all the heads needed to be replaced.

Ford said a worker from the sprinkler company showed up to replace the heads and asked what would be done with all the old heads. Told that there were no plans for them, the worker agreed to replace all the heads for free if he could keep the old heads and sell them; one of Ford’s partners agreed.

“Evidently there was enough of a market for the heads of this age, that were this ancient, that the guy could make money out of the deal,” Ford said, laughing.

While the original sprinkler heads are gone, many remnants of the area’s industrial history still remain. With the city’s rezoning opening the door to new development, memories such as Ford’s will be the link to the history the city hopes to preserve — memories including trout fishing. Ford said when he first moved into the building in 1970, he traveled to Melrose’s downtown for lunch. Entering a crowded restaurant, he shared a table with an elderly gentleman and before long, they were chatting. Ford mentioned he had just bought 72 Stone Place and the man asked if he knew where the Town Estates were — the apartment complex just up from Washington Street. “He said, ‘The brook used to run through there when I was kid’ – that had to be back in the early part of the century – and he said, ‘Used to be good trout fishing in there.’”

Reproduced from: https://www.longleaflumber.com/boston-rubber-shoe-company/:

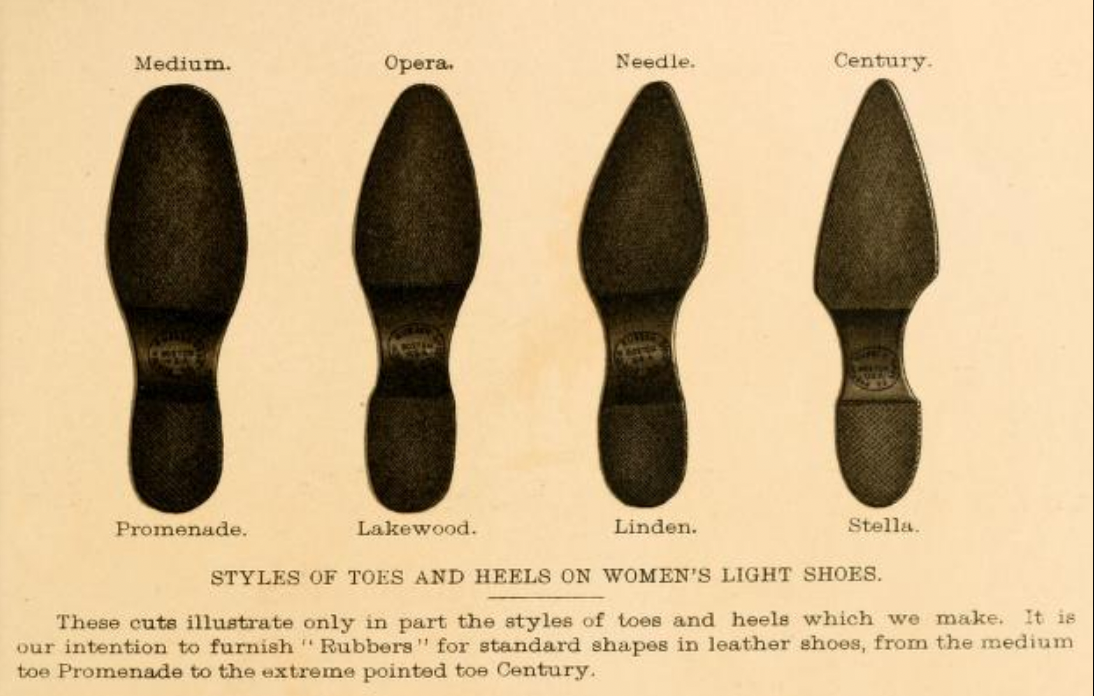

At its start, the Boston Rubber Shoe Company used the newly discovered vulcanized rubber to make just a few kinds of footwear. Their first factory, in nearby Malden, grew to employ 1,500 workers producing 20,000 pairs of shoes each day. Even this tremendous output, however, could not keep up with demand, so a second factory was built in 1883 on Washington Street in Melrose. This second site, called the Fells factory, or Factory No. 2, would employ 1,200 workers turning out an additional 12,000 pairs of shoes each day. Additional buildings were added to the mill complex in the 1890s, including 37 Washington Street. By 1899, the factories were producing 55,000 pairs of shoes each day in over 1,500 styles, shapes, and widths. In one nine-year period, the company produced nearly twelve million pairs of their most popular “Storm Slipper”. Shoes from Malden and Melrose were sold all over the country and around the world.

The Boston Rubber Shoe Company became the largest employer in Melrose and was largely responsible for the transformation of the city from a farming community to one with an industrial-residential character, as farms were sold and developed into housing lots for factory workers. The company was acquired in 1899 (5 years before Elisha’s death) by the U.S. Rubber Company, which consolidated operations and eventually closed the Melrose factory in 1929.

Article reproduced from https://bostonbasinhills.org/pages/melrose-hills.html.

Starting from a humble background, Elisha had worked on a farm, then in a clothing business before moving to Boston in 1844 to work with his elder brother James W. Converse and his uncles in their shoe and leather business. In 1847, with a partner and financial help from his brother, he bought the William Barrett’s grinding and rolling mill in Stoneham to process drugs and spices. In 1851, he became one of the founders of the First Malden Bank. In 1853 Elisha was offered the position of treasurer of the Malden Manufacturing Company. It had bought the building, machinery, and business of the failed Edgeworth Rubber Company.

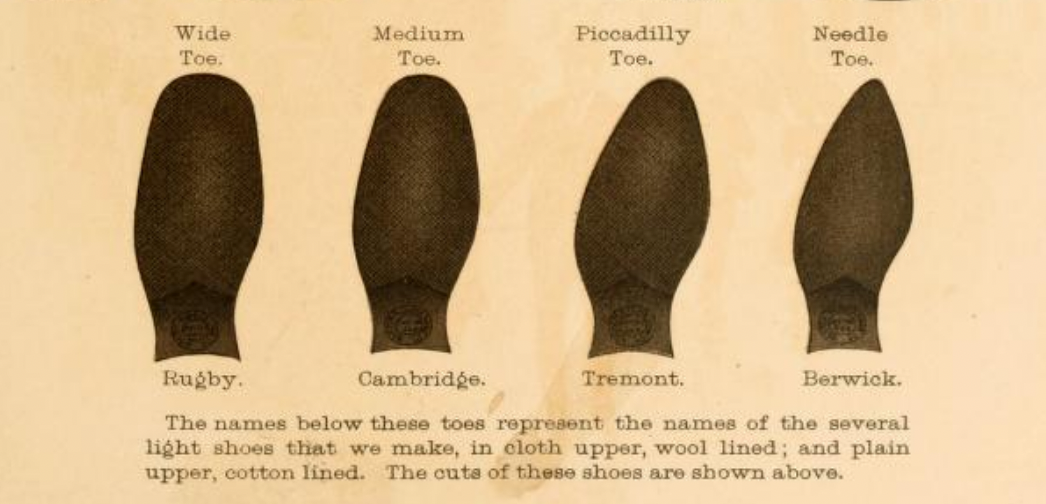

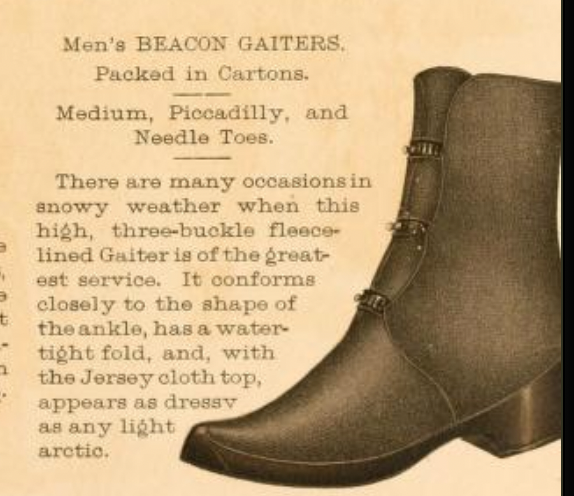

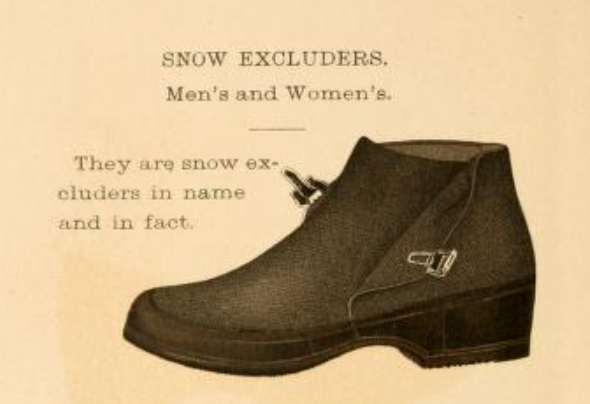

Below: Boston Rubber Shoe Co. catalog, 1896-1897- Internet Archive

It’s difficult to imagine a time now, with our non-slip toothbrush handles and memory foam beds, when rubber was brand new. In the early 1800s, the flexible waterproof substance from the Amazon rain forest promised to revolutionize both consumer and industrial products, with millions being invested in the “rubber boom.” Unfortunately, natural rubber melted in warm weather and froze in the cold, leading to the failure of business attempting to use the new substance. It was in locations around Boston that Charles Goodyear developed his vulcanization process that revolutionized the industry. The Roxbury Rubber Company in 1833 and 1834 had produced and sold large quantities of shoes and coats using a different process. In the succeeding summer, most melted and were returned, ultimately buried in a landfill. It was officials at the Roxbury Company that initially funded Goodyear, and it was in Woburn in 1839 that he made his momentous discovery, reportedly by accident when he dropped some uncured rubber onto a hot stove. It would be at a small factory in Springfield, Mass. in 1844 when Goodyear was confident enough in the development of the process that he would apply for a patent.

For Elisha Converse in 1853, two considerations likely influenced his decision to work in an industry where so many companies had failed before. First, the company had access to the Goodyear patent based on its board of directors, including a personal friend and legal advisor to Charles Goodyear, and Nathaniel Hayward, the person who worked with Goodyear in Woburn, and who some think should be entitled to equal credit for the discoveries of the process to vulcanize rubber. Second, Elisha, and his brother James, knew the shoe business, and likely had a good idea how revolutionary their product would be. The name of the company was changed to the Boston Rubber Shoe Company in 1855, and Elisha took on the additional roles of buying and selling agent, and eventually general manager and president. By 1880, the company was well on its way to becoming the world’s largest manufacturer of rubber boots and shoes, and looking to build another factory. The area around Pine Banks was available and Elisha purchased it and built a new factory between the hills of Pine Banks and the Middlesex Fells. Pine Banks itself was initially laid out to be subdivided into individual lots, but that never happened. Elisha and his wife Mary had a large mansion in Malden, and initially used Pine Banks as an exclusive park, building several log cabin retreats. But by 1890, Elisha had opened the park to the public, and when he died in 1904, his will proposed a public park jointly run by Malden and Melrose.

(Above: Proposed Roads and Lots, Pine Banks Park - MACRIS, Massachusetts Historical Commission)

For the citizens of Malden, Elisha Converse was a respected citizen and a notable philanthropist. He was elected Malden’s first mayor when it became a city in 1882. Earlier, he had been elected to the Massachusetts house of representatives, and then state senate. A tragic incident for the Converse family happened in 1863 when Harry Converse, Elisha’s and Mary’s first-born son was murdered while he was working as a cashier at his father’s bank. As a tribute to their son, Elisha purchased the land and paid for the design (by noted architect Henry R. Richardson), construction, and furnishing of the Malden Public Library. He also made substantial contributions for the establishment and construction of the Malden Hospital, City Hall, Historical Society, Home for Aged Persons, Day Nursery, a public school, and a Baptist Church. After a fire destroyed his factory is 1875, he constructed a reservoir and donated it to the town with that understanding that the water if needed could be used to fight another fire, today’s Fellsmere Park.

While Elisha’s brother James W. Converse had the title president of the Boston Rubber Shoe Company, it appears that he was more active in other endeavors.12 He still was president of the original Field Converse leather company, also founder, director and eventually president of the Mechanics Bank in Boston. A Deacon in the Baptist church, he was a major benefactor to the Tremont Temple Church in Boston with Converse Hall named for him. Elisha donated the organ in the hall. in 1850, James went to Grand Rapids, Mich. to straighten out a land ownership issue of the Baptist Mission. While there he noticed the significant gypsum deposits in the area used for stucco and plaster. He purchased large tracts of land for development, and gypsum mills. He then financed a railroad providing access to the area and established the Phoenix Furniture Company. Back in Boston, he and his son were trustees in the Boston Land Company and its efforts to develop the recently filled marshes in east Boston and Orient Heights. He was appointed receiver of the Hartford and Erie railroad, and made speculative investments in the Colorado Smelting Company.